-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 1

Style guide for Flutter repo

This document contains some high-level philosophy and policy decisions for the Minitel project, and a description of specific style issues for some parts of the codebase.

The style guide describes the preferred style for code written as part of the Flutter project (the framework itself and all our sample code). Flutter application developers are welcome to follow this style as well, but this is by no means required. Flutter will work regardless of what style is used to author applications that use it.

- Introduction

- Table of Contents

- Overview

-

Philosophy

- Lazy programming

- Write Test, Find Bug

- Avoid duplicating state

- Getters feel faster than methods

- No synchronous slow work

- Layers

- Avoid complecting (braiding multiple concepts together)

- Avoid secret (or global) state

- Prefer general APIs, but use dedicated APIs where there is a reason

- Avoid APIs that encourage bad practices

- Avoid exposing API cliffs

- Avoid exposing API oceans

- Solve real problems by literally solving a real problem

- Get early feedback when designing new APIs

- Policies

-

Documentation (dartdocs, javadocs, etc)

- Answer your own questions straight away

- Avoid useless documentation

- Writing prompts for good documentation

- Avoid empty prose

- Leave breadcrumbs in the comments

- Refactor the code when the documentation would be incomprehensible

- Canonical terminology

- Provide sample code

- Provide illustrations, diagrams or screenshots

- Clearly mark deprecated APIs

- Use

///for public-quality private documentation - Use correct grammar

- Dartdoc-specific requirements

-

Coding patterns and catching bugs early

- Use asserts liberally to detect contract violations and verify invariants

- Prefer specialized functions, methods and constructors

- Minimize the visibility scope of constants

- Avoid using

ifchains or?:or==with enum values - Avoid using

var - Avoid using

libraryandpart of. - Never check if a port is available before using it, never add timeouts, and other race conditions.

- Avoid mysterious and magical numbers that lack a clear derivation

- Have good hygiene when using temporary directories

- Perform dirty checks in setters

- Common boilerplates for

operator ==andhashCode - Override

toString

-

Naming

- Begin global constant names with prefix "k"

- Avoid abbreviations

- Naming rules for typedefs and function variables

- Spell words in identifiers and comments correctly

- Capitalize identifiers consistent with their spelling

- Avoid double negatives in APIs

- Prefer naming the argument to a setter

value - Qualify variables and methods used only for debugging

- Avoid naming undocumented libraries

- Comments

-

Formatting

- In defense of the extra work that hand-formatting entails

- Constructors come first in a class

- Order other class members in a way that makes sense

- Constructor syntax

- Prefer a maximum line length of 80 characters

- Indent multi-line argument and parameter lists by 2 characters

- If you have a newline after some opening punctuation, match it on the closing punctuation.

- Use a trailing comma for arguments, parameters, and list items, but only if they each have their own line.

- Prefer single quotes for strings

- Consider using

⇒for short functions and methods - Use

⇒for inline callbacks that just return list or map literals - Use braces for long functions and methods

- Separate the 'if' expression from its statement

- Align expressions

- Packages

This document describes our approach to designing and programming Flutter, from high-level architectural principles all the way to indentation rules.

The primary goal of these style guidelines is to improve code readability so that everyone, whether reading the code for the first time or maintaining it for years, can quickly determine what the code does. Secondary goals are to design systems that are simple, to increase the likelihood of catching bugs quickly, and avoiding arguments when there are disagreements over subjective matters.

For anything not covered by this document, check the Dart style guide for more advice. That document is focused primarily on Dart-specific conventions, while this document is more about Flutter conventions.

Designing an API is an art. Like all forms of art, one learns by practicing. The best way to get good at designing APIs is to spend a decade or more designing them, while working closely with people who are using your APIs. Ideally, one would first do this in very controlled situations, with small numbers of developers using one’s APIs, before graduating to writing APIs that will be used by hundreds of thousands or even millions of developers.

In the absence of one’s own experience, one can attempt to rely on the experience of others. The biggest problem with this is that sometimes explaining why an API isn’t optimal is a very difficult and subtle task, and sometimes the reasoning doesn’t sound convincing unless you already have a lot of experience designing them.

Because of this, and contrary to almost any other situation in engineering, when you are receiving feedback about API design from an experience API designer, they will sometimes seem unhappy without quite being able to articulate why. When this happens, seriously consider that your API should be scrapped and a new solution found.

This requires a different and equally important skill when designing APIs: not getting attached to one’s creations. One should try many wildly different APIs, and then attempt to write code that uses those APIs, to see how they work. Throw away APIs that feel frustrating, that lead to buggy code, or that other people don’t like. If it isn’t elegant, it’s usually better to try again than to forge ahead.

An API is for life, not just for the one PR you are working on.

Write what you need and no more, but when you write it, do it right.

Avoid implementing features you don’t need. You can’t design a feature without knowing what the constraints are. Implementing features "for completeness" results in unused code that is expensive to maintain, learn about, document, test, etc.

When you do implement a feature, implement it the right way. Avoid workarounds. Workarounds merely kick the problem further down the road, but at a higher cost: someone will have to relearn the problem, figure out the workaround and how to dismantle it (and all the places that now use it), and implement the feature. It’s much better to take longer to fix a problem properly, than to be the one who fixes everything quickly but in a way that will require cleaning up later.

You may hear team members say "embrace the yak shave!". This is an encouragement to take on the larger effort necessary to perform a proper fix for a problem rather than just applying a band-aid.

When you fix a bug, first write a test that fails, then fix the bug and verify the test passes.

When you implement a new feature, write tests for it. See also: Running and writing tests.

Check the code coverage to make sure every line of your new code is tested. See also: Test coverage.

If something isn’t tested, it is very likely to regress or to get "optimized away". If you want your code to remain in the codebase, you should make sure to test it.

Don’t submit code with the promise to "write tests later". Just take the time to write the tests properly and completely in the first place.

There should be no objects that represent live state that reflect

some state from another source, since they are expensive to maintain.

(The Web’s HTMLCollection object is an example of such an object.)

In other words, keep only one source of truth, and don’t replicate

live state.

Property getters should be efficient (e.g. just returning a cached

value, or an O(1) table lookup). If an operation is inefficient, it

should be a method instead. (Looking at the Web again: we would have

document.getForms(), not document.forms, since it walks the entire tree).

Similarly, a getter that returns a Future should not kick-off the work represented by the future, since getters appear idempotent and side-effect free. Instead, the work should be started from a method or constructor, and the getter should just return the preexisting Future.

There should be no APIs that require synchronously completing an expensive operation (e.g. computing a full app layout outside of the layout phase). Expensive work should be asynchronous.

We use a layered framework design, where each layer addresses a

narrowly scoped problem and is then used by the next layer to solve

a bigger problem. This is true both at a high level (widgets relies

on rendering relies on painting) and at the level of individual

classes and methods (e.g. Text uses RichText and DefaultTextStyle).

Convenience APIs belong at the layer above the one they are simplifying.

Each API should be self-contained and should not know about other features. Interleaving concepts leads to complexity.

For example:

-

Many Widgets take a

child. Widgets should be entirely agnostic about the type of that child. Don’t useisor similar checks to act differently based on the type of the child. -

Render objects each solve a single problem. Rather than having a render object handle both clipping and opacity, we have one render object for clipping, and one for opacity.

-

In general, prefer immutable objects over mutable data. Immutable objects can be passed around safely without any risk that a downstream consumer will change the data. (Sometimes, in Flutter, we pretend that some objects are immutable even when they technically are not: for example, widget child lists are often technically implemented by mutable

Listinstances, but the framework will never modify them and in fact cannot handle the user modifying them.) Immutable data also turns out to make animations much simpler through lerping.

A function should operate only on its arguments and, if it is an instance method, data stored on its object. This makes the code significantly easier to understand.

For example, when reading this code:

// ... imports something that defines foo and bar ...

void main() {

foo(1);

bar(2);

}…the reader should be confident that nothing in the call to foo could affect anything in the

call to bar.

This usually means structuring APIs so that they either take all relevant inputs as arguments, or so that they are based on objects that are created with the relevant input, and can then be called to operate on those inputs.

This significantly aids in making code testable and in making code understandable and debuggable. When code operates on secret global state, it’s much harder to reason about.

For example, having dedicated APIs for performance reasons is fine. If one specific operation, say clipping a rounded rectangle, is expensive using the general API but could be implemented more efficiently using a dedicated API, then that is where we would create a dedicated API.

For example, don’t provide APIs that walk entire trees, or that encourage O(N^2) algorithms, or that encourage sequential long-lived operations where the operations could be run concurrently.

In particular:

-

String manipulation to generate data or code that will subsequently be interpreted or parsed is a bad practice as it leads to code injection vulnerabilities.

-

If an operation is expensive, that expense should be represented in the API (e.g. by returning a

Futureor aStream). Avoid providing APIs that hide the expense of tasks.

Convenience APIs that wrap some aspect of a service from one environment for exposure in another environment (for example, exposing an Android API in Dart), should expose/wrap the complete API, so that there’s no cognitive cliff when interacting with that service (where you are fine using the exposed API up to a point, but beyond that have to learn all about the underlying service).

APIs that wrap underlying services but prevent the underlying API from

being directly accessed (e.g. how dart:ui exposes Skia) should carefully

expose only the best parts of the underlying API. This may require refactoring

features so that they are more usable. It may mean avoiding exposing

convenience features that abstract over expensive operations unless there’s a

distinct performance gain from doing so. A smaller API surface is easier

to understand.

For example, this is why dart:ui doesn’t expose Path.fromSVG(): we checked,

and it is just as fast to do that work directly in Dart, so there is no benefit

to exposing it. That way, we avoid the costs (bigger API surfaces are more

expensive to maintain, document, and test, and put a compatibility burden on

the underlying API).

Where possible, especially for new features, you should partner with a real customer who wants that feature and is willing to help you test it. Only by actually using a feature in the real world can we truly be confident that a feature is ready for prime time.

Listen to their feedback, too. If your first customer is saying that your feature doesn’t actually solve their use case completely, don’t dismiss their concerns as esoteric. Often, what seems like the problem when you start a project turns out to be a trivial concern compared to the real issues faced by real developers.

This section defines some policies that we have decided to honor. In the absence of a very specific policy in this section, the general philosophies in the section above are controlling.

We guarantee that a plugin published with a version equal to or greater than 1.0.0 will require no more recent a version of Flutter than the latest stable release at the time that the plugin was released. (Plugins may support older versions too, but that is not guaranteed.)

We are willing to implement temporary (one week or less) workarounds (e.g. //ignore hacks) if it helps a high profile developer or prolific contributor with a painful transition. Please contact @Darkness4 ([email protected]) if you need to make use of this option.

Code that is no longer maintained should be deleted or archived in some way that clearly indicates that it is no longer maintained.

For example, we delete rather than commenting out code. Commented-out code will bitrot too fast to be useful, and will confuse people maintaining the code.

Similarly, all our repositories should have an owner that does regular triage of incoming issues and PRs, and fixes known issues. Repositories where nobody is doing triage at least monthly, preferably more often, should be deleted, hidden, or otherwise archived.

We use "dartdoc" for our Dart documentation, and similar technologies for the documentation of our APIs in other languages, such as ObjectiveC and Java. All public members in Flutter libraries should have a documentation.

In general, follow the Dart documentation guide except where that would contradict this page.

When working on Flutter, if you find yourself asking a question about our systems, please place whatever answer you subsequently discover into the documentation in the same place where you first looked for the answer. That way, the documentation will consist of answers to real questions, where people would look to find them. Do this right away; it’s fine if your otherwise-unrelated PR has a bunch of documentation fixes in it to answer questions you had while you were working on your PR.

We try to avoid reliance on "oral tradition". It should be possible for anyone to begin contributing without having had to learn all the secrets from existing team members. To that end, all processes should be documented (typically on the wiki), code should be self-explanatory or commented, and conventions should be written down, e.g. in our style guide.

There is one exception: it’s better to not document something in our API docs than to document it poorly. This is because if you don’t document it, it still appears on our list of things to document. Feel free to remove documentation that violates our the rules below (especially the next one), so as to make it reappear on the list.

If someone could have written the same documentation without knowing anything about the class other than its name, then it’s useless.

Avoid checking in such documentation, because it is no better than no documentation but will prevent us from noticing that the identifier is not actually documented.

Example (from CircleAvatar):

// BAD:

/// The background color.

final Color backgroundColor;

/// Half the diameter of the circle.

final double radius;

// GOOD:

/// The color with which to fill the circle. Changing the background

/// color will cause the avatar to animate to the new color.

final Color backgroundColor;

/// The size of the avatar. Changing the radius will cause the

/// avatar to animate to the new size.

final double radius;If you are having trouble coming up with useful documentation, here are some prompts that might help you write more detailed prose:

-

If someone is looking at this documentation, it means that they have a question which they couldn’t answer by guesswork or by looking at the code. What could that question be? Try to answer all questions you can come up with.

-

If you were telling someone about this property, what might they want to know that they couldn’t guess? For example, are there edge cases that aren’t intuitive?

-

Consider the type of the property or arguments. Are there cases that are outside the normal range that should be discussed? e.g. negative numbers, non-integer values, transparent colors, empty arrays, infinities, NaN, null? Discuss any that are non-trivial.

-

Does this member interact with any others? For example, can it only be non-null if another is null? Will this member only have any effect if another has a particular range of values? Will this member affect whether another member has any effect, or what effect another member has?

-

Does this member have a similar name or purpose to another, such that we should point to that one, and from that one to this one? Use the

See also:pattern. -

Are there timing considerations? Any potential race conditions?

-

Are there lifecycle considerations? For example, who owns the object that this property is set to? Who should

dispose()it, if that’s relevant? -

What is the contract for this property/method? Can it be called at any time? Are there limits on what values are valid? If it’s a

finalproperty set from a constructor, does the constructor have any limits on what the property can be set to? If this is a constructor, are any of the arguments not nullable? -

If there are `Future`s involved, what are the guarantees around those? Consider whether they can complete with an error, whether they can never complete at all, what happens if the underlying operation is canceled, and so forth.

It’s easy to use more words than necessary. Avoid doing so where possible, even if the result is somewhat terse.

// BAD:

/// Note: It is important to be aware of the fact that in the

/// absence of an explicit value, this property defaults to 2.

// GOOD:

/// Defaults to 2.In particular, avoid saying "Note:". It adds nothing.

This is especially important for documentation at the level of classes.

If a class is constructed using a builder of some sort, or can be obtained via some mechanism other than merely calling the constructor, then include this information in the documentation for the class.

If a class is typically used by passing it to a particular API, then include that information in the class documentation also.

If a method is the main mechanism used to obtain a particular object, or is the main way to consume a particular object, then mention that in the method’s description.

Typedefs should mention at least one place where the signature is used.

These rules result in a chain of breadcrumbs that a reader can follow to get from any class or method that they might think is relevant to their task all the way up to the class or method they actually need.

Example:

// GOOD:

/// An object representing a sequence of recorded graphical operations.

///

/// To create a [Picture], use a [PictureRecorder].

///

/// A [Picture] can be placed in a [Scene] using a [SceneBuilder], via

/// the [SceneBuilder.addPicture] method. A [Picture] can also be

/// drawn into a [Canvas], using the [Canvas.drawPicture] method.

abstract class Picture ...You can also use "See also" links, is in:

/// See also:

///

/// * [FooBar], which is another way to peel oranges.

/// * [Baz], which quuxes the wibble.Each line should end with a period. Prefer "which…" rather than parentheticals on such lines. There should be a blank line between "See also:" and the first item in the bulleted list.

If writing the documentation proves to be difficult because the API is convoluted, then rewrite the API rather than trying to document it.

The documentation should use consistent terminology:

-

method - a member of a class that is a non-anonymous closure

-

function - a callable non-anonymous closure that isn’t a member of a class

-

parameter - a variable defined in a closure signature and possibly used in the closure body.

-

argument - the value passed to a closure when calling it.

Prefer the term "call" to the term "invoke" when talking about jumping to a closure.

Typedef dartdocs should usually start with the phrase "Signature for…".

Sample code helps developers learn your API quickly. Writing sample code also helps you think through how your API is going to be used by app developers.

Sample code should go in a section of the documentation that begins with {@tool sample}, and ends with {@end-tool}. This will then be checked by automated tools, and extracted and formatted for display on the API documentation web site docs.flutter.io.

For example, below is the sample code for building an infinite list of children with the ListView widget, as it would appear in the Flutter source code for the ListView widget:

/// A scrollable list of widgets arranged linearly.

///

/// ...

///

/// {@tool sample}

/// An infinite list of children:

///

/// ```dart

/// ListView.builder(

/// padding: EdgeInsets.all(8.0),

/// itemExtent: 20.0,

/// itemBuilder: (BuildContext context, int index) {

/// return Text('entry $index');

/// },

/// )

/// ```

/// {@end-tool}

class ListView {

// ...Our UI research has shown that developers prefer to see examples that are in the context of an entire app. So, whenever it makes sense, provide an example that can be presented as part of an entire application instead of just a simple sample like the one above.

This can be done using the {@tool snippet --template=<template>} … {@end-tool} dartdoc indicators, where <template> is the name of a template that the given blocks of dart code can be inserted into. See here for more details about writing these kinds of examples, and here for a list and description of the available templates.

Application examples will be presented on the API documentation website along with information about how to instantiate the example as an application that can be run. IDEs viewing the Flutter source code may also offer the option of creating a new project with the example.

For any widget that draws pixels on the screen, showing how it looks like in its API doc helps developers decide if the widget is useful and learn how to customize it. All illustrations should be easily reproducible, e.g. by running a Flutter app or a script.

Examples:

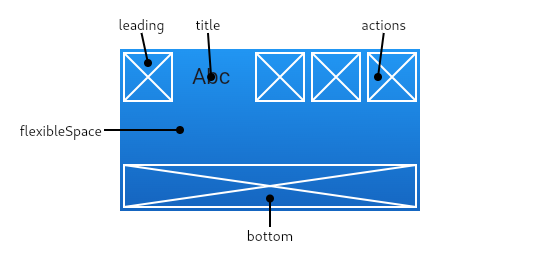

-

A diagram for the AppBar widget

-

A screenshot for the Card widget

According to Flutter’s Design Principles,

use @deprecated with a clear

recommendation of what to use instead.

In some cases, using @deprecated will turn the tree red for longer than the Flutter team

can accommodate. In those cases, and when we want to give developers enough time to

move to the new API, you should use this format:

// GOOD

/// (Deprecated, use [lib.class] instead) Original one-line statement.

///

/// A longer, one-liner that explains the context for the deprecation.

///

/// The rest of the commentsIn general, private code can and should also be documented. If that documentation is of good enough

quality that we could include it verbatim when making the class public (i.e. it satisfies all the

style guidelines above), then you can use /// for those docs, even though they’re private.

Documentation of private APIs that is not of sufficient quality should only use //. That way, if

we ever make the corresponding class public, those documentation comments will be flagged as missing,

and we will know to examine them more carefully.

Feel free to be conservative in what you consider "sufficient quality". It’s ok to use // even if

you have multiple paragraphs of documentation; that’s a sign that we should carefully rereview the

documentation when making the code public.

Avoid starting a sentence with a lowercase letter.

// BAD

/// [foo] must not be null.

// GOOD

/// The [foo] argument must not be null.Similarly, end all sentences with a period.

The first paragraph of any dartdoc section must be a short self-contained sentence that explains the purpose and meaning of the item being documented. Subsequent paragraphs then must elaborate. Avoid having the first paragraph have multiple sentences. (This is because the first paragraph gets extracted and used in tables of contents, etc, and so has to be able to stand alone and not take up a lot of room.)

When referencing an argument, use backticks. However, when referencing an argument that also corresponds to a property, use square brackets instead.

// GOOD

/// Creates a foobar, which allows a baz to quux the bar.

///

/// The [bar] argument must not be null.

///

/// The `baz` argument must be greater than zero.

Foo({ this.bar, int baz }) : assert(bar != null), assert(baz > 0);Avoid using terms like "above" or "below" to reference one dartdoc section from another. Dartdoc sections are often shown alone on a Web page, the full context of the class is not present.

assert() allows us to be diligent about correctness without paying a

performance penalty in release mode, because Dart only evaluates asserts in

debug mode.

It should be used to verify contracts and invariants are being met as we expect. Asserts do not enforce contracts, since they do not run at all in release builds. They should be used in cases where it should be impossible for the condition to be false without there being a bug somewhere in the code.

The following example is from box.dart:

abstract class RenderBox extends RenderObject {

// ...

double getDistanceToBaseline(TextBaseline baseline, {bool onlyReal: false}) {

// simple asserts:

assert(!needsLayout);

assert(!_debugDoingBaseline);

// more complicated asserts:

assert(() {

final RenderObject parent = this.parent;

if (owner.debugDoingLayout)

return (RenderObject.debugActiveLayout == parent) &&

parent.debugDoingThisLayout;

if (owner.debugDoingPaint)

return ((RenderObject.debugActivePaint == parent) &&

parent.debugDoingThisPaint) ||

((RenderObject.debugActivePaint == this) && debugDoingThisPaint);

assert(parent == this.parent);

return false;

});

// ...

return 0.0;

}

// ...

}Use the most relevant constructor or method, when there are multiple options.

Example:

// BAD:

const EdgeInsets.TRBL(0.0, 8.0, 0.0, 8.0);

// GOOD:

const EdgeInsets.symmetric(horizontal: 8.0);Prefer using a local const or a static const in a relevant class than using a global constant.

Use switch if you are examining an enum, since the analyzer will warn you if you missed any of the

values when you use switch.

Avoid using if chains, ? … : …, or, in general, any expressions involving enums.

All variables and arguments are typed; avoid "dynamic" or "Object" in any case where you could figure out the actual type. Always specialize generic types where possible. Explicitly type all list and map literals.

This achieves two purposes: it verifies that the type that the compiler would infer matches the type you expect, and it makes the code self-documenting in the case where the type is not obvious (e.g. when calling anything other than a constructor).

Always avoid "var". Use "dynamic" if you are being explicit that the

type is unknown, but prefer "Object" and casting, as using dynamic

disables all static checking.

Prefer that each library be self-contained. Only name a library if you are documenting it (see the

documentation section).

We avoid using part of because that feature makes it very hard to reason about how private a private

really is, and tends to encourage "spaghetti" code (where distant components refer to each other) rather

than "lasagna" code (where each section of the code is cleanly layered and separable).

If you look for an available port, then try to open it, it’s extremely likely that several times a week some other code will open that port between your check and when you open the port, and that will cause a failure.

Instead, have the code that opens the port pick an available port and return it, rather than being given a (supposedly) available port.

If you have a timeout, then it’s very likely that several times a week some other code will happen to run while your timeout is running, and your "really conservative" timeout will trigger even though it would have worked fine if the timeout was one second longer, and that will cause a failure.

Instead, have the code that would time out just display a message saying that things are unexpectedly taking a long time, so that someone interactively using the tool can see that something is fishy, but an automated system won’t be affected.

Race conditions like this are the primary cause of flaky tests, which waste everyone’s time.

Numbers in tests and elsewhere should be clearly understandable. When the provenance of a number is not obvious, consider either leaving the expression or adding a clear comment (bonus points for leaving a diagram).

// BAD

expect(rect.left, 4.24264068712);

// GOOD

expect(rect.left, 3.0 * math.sqrt(2));Give the directory a unique name that starts with flutter_ and ends with a period (followed by the autogenerated random string).

For consistency, name the Directory object that points to the temporary directory tempDir, and create it with createTempSync unless you need to do it asynchronously (e.g. to show progress while it’s being created).

Always clean up the directory when it is no longer needed. In tests, use the tryToDelete convenience function to delete the directory.

Dirty checks are processes to determine whether a changed values have been synchronized with the rest of the app.

When defining mutable properties that mark a class dirty when set, use the following pattern:

/// Documentation here (don't wait for a later commit).

TheType get theProperty => _theProperty;

TheType _theProperty;

void set theProperty(TheType value) {

assert(value != null);

if (_theProperty == value)

return;

_theProperty = value;

markNeedsWhatever(); // the method to mark the object dirty

}The argument is called 'value' for ease of copy-and-paste reuse of this pattern. If for some reason you don’t want to use 'value', use 'newProperty' (where 'Property' is the property name).

Start the method with any asserts you need to validate the value.

We have many classes that override operator == and hashCode ("value classes"). To keep the code consistent,

we use the following style for these methods:

@override

bool operator ==(Object other) {

if (other.runtimeType != runtimeType)

return false;

final Foo typedOther = other;

return typedOther.bar == bar

&& typedOther.baz == baz

&& typedOther.quux == quux;

}

@override

int get hashCode => hashValues(bar, baz, quux);For objects with a lot of properties, consider adding the following at the top of the operator ==:

if (identical(other, this))

return true;(We don’t yet use this exact style everywhere, so feel free to update code you come across that isn’t yet using it.)

In general, consider carefully whether overriding operator == is a good idea. It can be expensive, especially

if the properties it compares are themselves comparable with a custom operator ==. If you do override equality,

you should use @immutable on the class hierarchy in question.

Use Diagnosticable (rather than directly overriding toString) on all but the most trivial classes. That allows us to inspect the object from devtools and IDEs.

For trivial classes, override toString as follows, to aid in debugging:

@override

String toString() => '$runtimeType($bar, $baz, $quux)';…but even then, consider using Diagnosticable instead.

Examples:

const double kParagraphSpacing = 1.5;

const String kSaveButtonTitle = 'Save';

const Color _kBarrierColor = Colors.black54;However, where possible avoid global constants. Rather than kDefaultButtonColor, consider Button.defaultColor. If necessary, consider creating a class with a private constructor to hold relevant constants. It’s not necessary to add the k prefix to non-global constants.

Unless the abbreviation is more recognizable than the expansion (e.g. XML, HTTP, JSON), expand abbrevations

when selecting a name for an identifier. In general, avoid one-character names unless one character is idiomatic

(for example, prefer index over i, but prefer x over horizontalPosition).

When naming callbacks, use FooCallback for the typedef, onFoo for

the callback argument or property, and handleFoo for the method

that is called.

If you have a callback with arguments but you want to ignore the arguments, give the type and names of the arguments anyway. That way, if someone copies and pastes your code, they will not have to look up what the arguments are.

Never call a method onFoo. If a property is called onFoo it must be

a function type. (For all values of "Foo".)

Our primary source of truth for spelling is the Material Design Specification. Our secondary source of truth is dictionaries.

Avoid "cute" spellings. For example, 'colors', not 'colorz'.

Prefer US English spellings. For example, 'colorize', not 'colourise'.

Prefer compound words over "cute" spellings to avoid conflicts with reserved words. For example, 'classIdentifier', not 'klass'.

If a word is correctly spelled (according to our sources of truth as described in the previous section) as a single word, then it should not have any inner capitalization or spaces.

For examples, prefer toolbar, scrollbar, but appBar ('app bar' in documentation), tabBar ('tab bar' in documentation).

Similarly, prefer offstage rather than offStage.

Avoid starting class names with iOS since that would have to capitalize as Ios which is not how that is spelled. (Use "Cupertino" or "UiKit" instead.)

Name your boolean variables in positive ways, such as "enabled" or "visible", even if the default value is true.

This is because, when you have a property or argument named "disabled" or "hidden", it leads to code such as input.disabled = false or widget.hidden = false when you’re trying to enable or show the widget, which is very confusing.

Unless this would cause other problems, use value for the name of a setter’s argument. This makes it easier to copy/paste the setter later.

If you have variables or methods (or even classes!) that are only used in debug mode,

prefix their names with debug or _debug (or, for classes, _Debug).

Do not use debugging variables or methods (or classes) in production code.

Find the answers to the questions, or describe the confusion, including references to where you found answers.

If commenting on a workaround due to a bug, also leave a link to the bug and a TODO to clean it up when the bug is fixed.

Example:

// BAD:

// What should this be?

// This is a workaround.

// GOOD:

// According to this specification, this should be 2.0, but according to that

// specification, it should be 3.0. We split the difference and went with

// 2.5, because we didn't know what else to do.

// TODO(username): Converting color to RGB because class Color doesn't support

// hex yet. See http://link/to/a/bug/123Sometimes, it is necessary to write code that the analyzer is unhappy with.

If you find yourself in this situation, consider how you got there. Is the analyzer actually correct but you don’t want to admit it? Think about how you could refactor your code so that the analyzer is happy. If such a refactor would make the code better, do it. (It might be a lot of work… embrace the yak shave.)

If you are really really sure that you have no choice but to silence the analyzer, use `// ignore: `. The ignore directive should be on the same line as the analyzer warning.

If the ignore is temporary (e.g. a workaround for a bug in the compiler or analyzer, or a workaround for some known problem in Flutter that you cannot fix), then add a link to the relevant bug, as follows:

foo(); // ignore: lint_code, https://link.to.bug/goes/hereIf the ignore directive is permanent, e.g. because one of our lints has some unavoidable false positives and in this case violating the lint is definitely better than all other options, then add a comment explaining why:

foo(); // ignore: lint_code, sadly there is no choice but to do

// this because we need to twiddle the quux and the bar is zorgle.These guidelines have no technical effect, but they are still important purely for consistency and readability reasons.

We do not yet use dartfmt. Flutter code tends to use patterns that

the standard Dart formatter does not handle well. We are

working with Dart team to make dartfmt aware of these patterns.

Flutter code might eventually be read by hundreds of thousands of people each day. Code that is easier to read and understand saves these people time. Saving each person even a second each day translates into hours or even days of saved time each day. The extra time spent by people contributing to Flutter directly translates into real savings for our developers, which translates to real benefits to our end users as our developers learn the framework faster.

The default (unnamed) constructor should come first, then the named constructors. They should come before anything else (including, e.g., constants or static methods).

This helps readers determine whether the class has a default implied constructor or not at a glance. If it was possible for a constructor to be anywhere in the class, then the reader would have to examine every line of the class to determine whether or not there was an implicit constructor or not.

The methods, properties, and other members of a class should be in an order that will help readers understand how the class works.

If there’s a clear lifecycle, then the order in which methods get invoked would be useful, for example an initState method coming before dispose. This helps readers because the code is in chronological order, so

they can see variables get initialized before they are used, for instance. Fields should come before the methods that manipulate them, if they are specific to a particular group of methods.

For example, RenderObject groups all the layout fields and layout methods together, then all the paint fields and paint methods, because layout happens before paint.

If no particular order is obvious, then the following order is suggested, with blank lines between each one:

-

Constructors, with the default constructor first.

-

Constants of the same type as the class.

-

Static methods that return the same type as the class.

-

Final fields that are set from the constructor.

-

Other static methods.

-

Static properties and constants.

-

Mutable properties, each in the order getter, private field, setter, without newlines separating them.

-

Read-only properties (other than

hashCode). -

Operators (other than

==). -

Methods (other than

toStringandbuild). -

The

buildmethod, forWidgetandStateclasses. -

operator ==,hashCode,toString, and diagnostics-related methods, in that order.

Be consistent in the order of members. If a constructor lists multiple fields, then those fields should be declared in the same order, and any code that operates on all of them should operate on them in the same order (unless the order matters).

If you call super() in your initializer list, put a space between the

constructor arguments' closing parenthesis and the colon. If there’s

other things in the initializer list, align the super() call with the

other arguments. Don’t call super if you have no arguments to pass up

to the superclass.

// one-line constructor example

abstract class Foo extends StatelessWidget {

Foo(this.bar, { Key key, this.child }) : super(key: key);

final int bar;

final Widget child;

// ...

}

// fully expanded constructor example

abstract class Foo extends StatelessWidget {

Foo(

this.bar, {

Key key,

Widget childWidget,

}) : child = childWidget,

super(

key: key,

);

final int bar;

final Widget child;

// ...

}Aim for a maximum line length of roughly 80 characters, but prefer going over if breaking the line would make it less readable, or if it would make the line less consistent with other nearby lines. Prefer avoiding line breaks after assignment operators.

// BAD (breaks after assignment operator and still goes over 80 chars)

final int a = 1;

final int b = 2;

final int c =

a.very.very.very.very.very.long.expression.that.returns.three.eventually().but.is.very.long();

final int d = 4;

final int e = 5;

// BETTER (consistent lines, not much longer than the earlier example)

final int a = 1;

final int b = 2;

final int c = a.very.very.very.very.very.long.expression.that.returns.three.eventually().but.is.very.long();

final int d = 4;

final int e = 5;// BAD (breaks after assignment operator)

final List<FooBarBaz> _members =

<FooBarBaz>[const Quux(), const Qaax(), const Qeex()];

// BETTER (only slightly goes over 80 chars)

final List<FooBarBaz> _members = <FooBarBaz>[const Quux(), const Qaax(), const Qeex()];

// BETTER STILL (fits in 80 chars)

final List<FooBarBaz> _members = <FooBarBaz>[

const Quux(),

const Qaax(),

const Qeex(),

];When breaking an argument list into multiple lines, indent the arguments two characters from the previous line.

Example:

Foo f = Foo(

bar: 1.0,

quux: 2.0,

);When breaking a parameter list into multiple lines, do the same.

And vice versa.

Example:

// BAD:

foo(

bar, baz);

foo(

bar,

baz);

foo(bar,

baz

);

// GOOD:

foo(bar, baz);

foo(

bar,

baz,

);

foo(bar,

baz);Use a trailing comma for arguments, parameters, and list items, but only if they each have their own line.

Example:

List<int> myList = [

1,

2,

]

myList = <int>[3, 4];

foo1(

bar,

baz,

);

foo2(bar, baz);Use double quotes for nested strings or (optionally) for strings that contain single quotes. For all other strings, use single quotes.

Example:

print('Hello ${name.split(" ")[0]}');But only use ⇒ when everything, including the function declaration, fits

on a single line.

Example:

// BAD:

String capitalize(String s) =>

'${s[0].toUpperCase()}${s.substring(1)}';

// GOOD:

String capitalize(String s) => '${s[0].toUpperCase()}${s.substring(1)}';

String capitalize(String s) {

return '${s[0].toUpperCase()}${s.substring(1)}';

}If your code is passing an inline closure that merely returns a list or

map literal, or is merely calling another function, then if the argument

is on its own line, then rather than using braces and a return statement,

you can instead use the ⇒ form. When doing this, the closing ], }, or

) bracket will line up with the argument name, for named arguments, or the

( of the argument list, for positional arguments.

For example:

// GOOD, but slightly more verbose than necessary since it doesn't use =>

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return PopupMenuButton<String>(

onSelected: (String value) { print('Selected: $value'); },

itemBuilder: (BuildContext context) {

return <PopupMenuItem<String>>[

PopupMenuItem<String>(

value: 'Friends',

child: MenuItemWithIcon(Icons.people, 'Friends', '5 new')

),

PopupMenuItem<String>(

value: 'Events',

child: MenuItemWithIcon(Icons.event, 'Events', '12 upcoming')

),

];

}

);

}

// GOOD, does use =>, slightly briefer

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return PopupMenuButton<String>(

onSelected: (String value) { print('Selected: $value'); },

itemBuilder: (BuildContext context) => <PopupMenuItem<String>>[

PopupMenuItem<String>(

value: 'Friends',

child: MenuItemWithIcon(Icons.people, 'Friends', '5 new')

),

PopupMenuItem<String>(

value: 'Events',

child: MenuItemWithIcon(Icons.event, 'Events', '12 upcoming')

),

]

);

}The important part is that the closing punctuation lines up with the start of the line that has the opening punctuation, so that you can easily determine what’s going on by just scanning the indentation on the left edge.

Use a block (with braces) when a body would wrap onto more than one line (as opposed to using ⇒; the cases where you can use ⇒ are discussed in the previous two guidelines).

Don’t put the statement part of an 'if' statement on the same line as the expression, even if it is short. (Doing so makes it unobvious that there is relevant code there. This is especially important for early returns.)

Example:

// BAD:

if (notReady) return;

// GOOD:

if (notReady)

return;

// ALSO GOOD:

if (notReady) {

return;

}Where possible, subexpressions on different lines should be aligned, to make the structure of the expression easier. When doing this with a return statement chaining || or && operators, consider putting the operators on the left hand side instead of the right hand side.

// BAD:

if (foo.foo.foo + bar.bar.bar * baz - foo.foo.foo * 2 +

bar.bar.bar * 2 * baz > foo.foo.foo) {

// ...

}

// GOOD (notice how it makes it obvious that this code can be simplified):

if (foo.foo.foo + bar.bar.bar * baz -

foo.foo.foo * 2 + bar.bar.bar * 2 * baz > foo.foo.foo) {

// ...

}

// After simplification, it fits on one line anyway:

if (bar.bar.bar * 3 * baz > foo.foo.foo * 2) {

// ...

}// BAD:

return foo.x == x &&

foo.y == y &&

foo.z == z;

// GOOD:

return foo.x == x &&

foo.y == y &&

foo.z == z;

// ALSO GOOD:

return foo.x == x

&& foo.y == y

&& foo.z == z;As per normal Dart conventions, a package should have a single import that reexports all of its API.

For example, rendering.dart exports all of lib/src/rendering/*.dart

If a package uses, as part of its exposed API, types that it imports from a lower layer, it should reexport those types.

For example, material.dart reexports everything from widgets.dart. Similarly, the latter reexports many types from rendering.dart, such as

BoxConstraints, that it uses in its API. On the other hand, it does not reexport, say,RenderProxyBox, since that is not part of the widgets API.

For the rendering.dart library, if you are creating new

RenderObject subclasses, import the entire library. If you are only

referencing specific RenderObject subclasses, then import the

rendering.dart library with a show keyword explicitly listing the

types you are importing. This latter approach is generally good for

documenting why exactly you are importing particularly libraries and

can be used more generally when importing large libraries for very

narrow purposes.

By convention, dart:ui is imported using import 'dart:ui' show

…; for common APIs (this isn’t usually necessary because a lower

level will have done it for you), and as import 'dart:ui' as ui show

…; for low-level APIs, in both cases listing all the identifiers

being imported. See

basic_types.dart

in the painting package for details of which identifiers we import

which way. Other packages are usually imported undecorated unless they

have a convention of their own (e.g. path is imported as path).

As a general rule, when you have a lot of constants, wrap them in a class. For examples of this, see lib/src/material/colors.dart.

Minitel Toolbox • Write Test Find Bug • Embrace the Yak Shave