So far we have talked about Proof-of-Work which is the protocol that Bitcoin uses to come to consensus. However, Bitcoin’s proof of work has a lot of problems, the biggest of which is scalability and energy consumption. Bitcoin is claimed to use up as much energy as the country Iceland. Furthermore, this energy consumption isn’t justified because a decentralized payment system that is much slower than any bank or centralized institution that exists today is not a viable replacement. If you were to buy coffee with bitcoin today, you would end up with cold coffee. Naturally, these are sufficient reasons why there is a need for alternative sybil control mechanisms. Proof-of-Stake is one of the most talked about sybil control mechanisms proposed. Ethereum, Cardano, EOS, Tendermint, Algorand, ThunderToken are some of the biggest projects which are all using Proof-of-Stake. In this chapter we will understand what Proof-of-stake is and why it is a scalable and energy efficient alternative to Proof-of-Work.

What is Proof of Stake?

Proof-of-Stake is an alternative decentralized sybil control protocol design family that can be layered on any consensus mechanism. The idea behind this family of protocols is that voting power is directly proportional to the stake or number of coins held by a “validator”. Validators perform the job that miners in proof-of-work perform, their responsibility is take care of the functioning of the blockchain network for which they are usually rewarded with transaction fees and block rewards. The belief is that stakeholders of the blockchain are economically rational and hence are incentivized to act honestly because the value of their money diminishes any time the trust in the blockchain system wanes. There are several ways of classifying the idea of Proof-of-Stake. One common way is based on if users can also gain a share of rewards in protocol by sending their rewards to validators that the user trusts and having the validator act on the user’s behalf also called as “delegating”. When the user can act as a delegator, the protocol is often classified as Delegated Proof-of-Stake. Another classification is along the lines of if the Proof-of-Stake protocol ensures that once a block has been added to the blockchain it will be considered as the final view and cannot be removed or forked at that height. This property is referred to as finality. “BFT based” Proof-of-Stakes ensure immediate finality at every block while “Chain based” Proof-of-Stakes use a concept of eventual finality or the idea that when many blocks are added on top of the current block the probability of the current block being replaced becomes very low. Proof-of-Stakes can have several other variations based on if rewards are given to validators, their randomness source, their network assumptions and many more parameters. For the rest of the chapter we focus on solely on Ethereum’s designs. To learn more about how these compare to other Proof-of-Stakes you can see this chart.

Naive Proof of Stake and the nothing at stake problem.

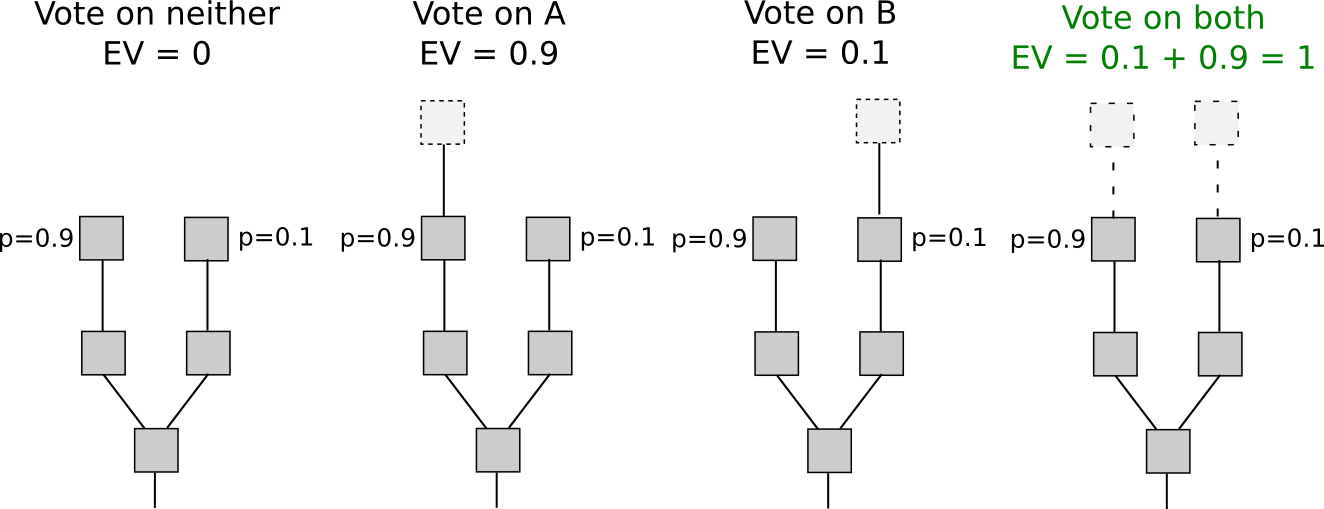

In early versions of proof of stake, specifically in chain based proof of stakes, there was nothing penalizing conflicting votes. This means that validators could vote on multiple conflicting histories without any repercussions. It was actually economically rational for validators to vote on multiple chains, since it would mean that they had a higher expected reward.

Nothing At Stake in Chain Based systems

Nothing At Stake in Chain Based systems

This is problematic because if there ever is a fork in the blockchain history, there is little incentive for anyone to ever resolve the fork. Thus, a chain based proof-of-stake system with no penalties and only rewards never comes to agreement on a single transaction history. This attack is called the nothing at stake problem because there is no penalty and only a reward for acting in a dishonest manner. Although one can argue that if someone holds a lot of stake, it is still in their incentive to eventually have the blockchain converge to ensure that the price of the staking token doesn’t fall drastically and incentivize more usage of the blockchain. Thus, nothing at stake might be an attack if proof of stake is modelled from the perspective of just one round, but if proof-of-stake is modelled from the perspective of multiple rounds it may no longer be an attack vector.

Solving nothing at stake by introducing slashing.

One way to present nothing at stake is by penalizing validators who vote on multiple conflicting histories. This is only a solution for systems where there are rewards. If there are no rewards, penalizing stakeholders would disincentivize them from participating. In order to penalize any malicious actor, detecting malicious behaviour is important. It is relatively easy to detect double signing of two conflicting histories at the same height. Thus any honest node who constructs and submits a proof of fraudulent behaviour as a transaction into the blockchain can redeem a reward for catching bad actors. The malicious validator in turn gets punished by losing some portion of their stake tokens. The threat of losing tokens disincentivizes validators from creating conflicting histories at the same height. There are multiple versions of slashing that have been thought about. One type of slashing is called slashing for voting on multiple chains, while another type of slashing tries to mimic proof-of-work by slashing a validator who votes on the wrong chain. The new payoff matrices look something like the ones below:

Slashing for voting on the multiple chains

Slashing for voting on the multiple chains

Slashing for voting on the wrong chain

Slashing for voting on the wrong chain

Slashing conditions case studies: Casper FFG

- Use proof of work to propose blocks (can also randomly sample to propose blocks)

- Vote on epochs every 50 blocks

- Slashing conditions: 1) NO_DBL_VOTE & 2) NO_SURROUND_VOTE

- 2/3 threshold for finality means we require 1/3 coins to be slashed if two histories finalize

- Formal verification: quick look at isabelle proof for casper slashing conditions, and discuss importance of both valiation and verification

Slashing Conditions Case Study: Casper FFG

Casper FFG is a chain based hybrid proof of stake that plans to use proof of work as the randomness generation mechanism to to propose blocks. However, proof-of-work only provides probabilistic finality. In order to ensure that any transaction included in the blockchain is not going to be displaced, finality is important. Proof-of-stake is layered at the end of every epoch i.e around 50 blocks to ensure finality in Casper FFG. Validators on casper can check for malicious behavior by looking out for the following two conditions:

- NO_DBL_VOTE

- NO_SURROUND_VOTE A general proof of stake round has a leader who proposes a certain value and requires ⅔ staking power to agree on the right value. The assumption that such a voting system makes is that there are less than ⅓ malicious actors in the system. In fact, because of the byzantine generals problem and impossibility result, the proof of stake mechanism needs this assumption to hold. This means that if we ever finalize two conflicting histories, then more than ⅓ of the staking power is in the hands malicious actors. This also means that ⅓ of the coins need to be slashed.

Advanced PoS Systems

Any Proof of stake system also needs to deal with Validator set changes i.e there should be different validators for different rounds. This is important for two reasons Permissionless: Any proof-of-stake system should also enable validators to go offline and come back online. This is important because initially there might be a lot of interest for people to join as a validator but if they don’t make a lot of rewards they might want to stop being validators. In bitcoin anyone can join or leave at any time that they want. This is what it means for a system to be permissionless. Scalability: This enables more people to participate as validators while ensuring that the system is scalable. Sending messages across the internet is expensive thus it is it becomes costly to have a huge validator set for every round of proof-of-stake. Casper ensures validators can join and leave as long as there is a sufficient bonding and unbonding period. Thus validator sets can only change once there are two consecutive finalized blocks. This is to defend against short range attacks i.e a validator forks the history and immediately unbonds thus cannot be slashed for acting badly. Another consideration with validator sets is to ensure that minority isn’t grieved or trapped in forever. If for example the majority is dishonest, then the minority will not be able to unbond their stake and leave the system because finality is never reached. In order to resist such an attack, we introduce leaking. Leaking allows minority validators to soft fork to their own chain, and then over a period of time, they will have control of a majority of stake on their soft fork chain. This allows them to reach finality & effectively coordinate a hard fork. The minority could always sell their private keys to the validator in the worst case, however that is not an ideal fall back mechanism because that leads to several signature based attacks. No one else might be willing to buy the private keys if they hear that the network is under attack and if the market doesn’t know that the network is under attack, such an attempt to sell keys will definitely inform the market and cause chaotic markets.

RanDAO block proposal

Proof of work is both a sybil control mechanism and a source of randomness. Casper FFG uses a hybrid of proof of stake and proof of work. In order to completely replace proof of work, one also needs a randomness generation mechanism. Randao is one approach to generate randomness. Randao uses a scheme called onion hashing described below: Hash a random value 10000 times, and then commit to the last hash in the chain. Each time it is your turn, you reveal the previous hash in the chain. This is checked against your last reveal eg. I reveal x_4 and it is checked with -- hash(x_4) == x_5. There are multiple other randomness generation schemes which are thoroughly analyzed.

Problems to try out Implement Casper FFG with no slashing

- Send

DEPOSITtransaction which makes you a validator. - Send

WITHDRAWto get your money back. - Sign

VOTEtransactions of the form[checkpoint_hash, target_epoch, source_epoch, sig] - When ⅔ votes are reached for two subsequent checkpoints, the first is finalized.

Extra credit Add slashing conditions!

In the previous chapter we took a look at what proof of stake means. In this chapter we will dive deeper and look into several attacks on proof of stake. PoS has several attacks unique to it that come with designing a system that relies on economic incentives.

The first part about analysing any PoS system is to understand how robust the system is against attacks. To be robust against attacks, a system should fundamentally be able to prevent, detect and finally punish dishonest activity.

In the previous chapter we talked about how PoS systems are designed in order to prevent someone from acting maliciously. In this chapter we will focus on the detection and punishment aspect of the security of PoS systems.

In order to punish malicious behavior, it is important to first be able to detect and attribute the fault to a certain malicious node. Fault attribution is broadly classified into 2 categories:

- Uniquely attributable faults

- There exists proof of who committed some fault and so we can attribute it to a unique actor.

- Egs. Double Spending attacks

- Non-uniquely attributable faults

- When faults occur and we cannot identify a single perpetrator.

- Egs. Offline nodes vs DoSing of a Node

Uniquely attributable faults enables the system to punish the malicious actor. Penalties for non-uniquely attributable faults must often be dispersed amongst all possible offenders. This means that people who did nothing wrong can receive penalties!

Griefing analysis An attacker may intentionally causes non-uniquely attributable faults in order to reduce someone else’s payoff. This is called griefing. We can analyze these griefing attacks with the reduction in attacker’s payoff vs reduction in victim payoffs. This ratio is called the griefing factor. A griefing factor of 1:1 means that for every unit of value the attacker loses in penalties, the victim node loses an equal amount. A griefing factor of 1:2 means for every unit of value the attacker loses, the victim loses twice that… and so on. Discouragement attacks A particular attack can be built out of griefing which is worth noting, this is the discouragement attack. In a discouragement attack, the attacker reduces the expected payoff for honest nodes. This can result in fewer honest nodes participating in the protocol. This attack can be coupled with subsequent attacks which take advantage of the honest node discouragement. In Casper FFG, a discouragement attack can look like the following:

- Discourage -- reduce the expected payoff for honest nodes by going offline to make honest nodes appear to be censoring.

- Wait -- Rational nodes will realize that their expected payoff has gone down, and so will withdraw their deposits and no longer participate in consensus.

- Attack -- Cause a safety failure. This will be significantly cheaper as many of the deposits will have been withdrawn. For a more thorough analysis framework of PoS you can see this chart

Attacks and Defenses using primitives:

Cryptographic attacks:

- Timing Attacks

- Grinding

- On Anti-Pre-Revelation Games

- Nothing at Stake

Game Theory attacks

- Selfish mining

- Bribing attacks

- Long Range

- The P + epsilon Attack

- Censorship

- The Problem of Censorship

- Pooling and related attacks

Network attacks

- Eclipse Attacks

- Timejacking

- Spam attacks

Distributed Systems perspective:

- On Settlement Finality